How would you structure a feed for syndicating blog content? Remember, it would need to be standard enough for a computer to read and parse it, but simple enough for a developer to implement. Specific enough for web publishers, blogs, podcasts and all sorts of media, but universal enough for edge cases. Not to mention well documented and easy to extend.

Well, these are the challenges Sam Ruby addressed in his blog post Anatomy of a Well Formed Log Entry, written in June of 2003. In less than than 500 words, he laid out an ideal format for web content syndication.

About a month later, he and some like-minded programmers created Atom.

To talk through the details of Atom, Ruby set up a public wiki, out in the open for everyone to see. He emphasized that for now, this was a high-level discussion not tied to any specific technologies. And the first step would be to create the perfect format for just blogs.

These were careful and deliberate decisions. And they were made, in large part, because the prevailing blog feed format was RSS. And RSS had become something of a confusing mess.

RSS, simply put, is a special type of web format designed specifically for computers, so that content can be syndicated through various types of software, the most common of which is probably the feed reader. But if you really want to understand RSS, you have to understand RDF. And RDF started with Ramanathan V. Guha.

Guha did his research at Apple in 1995, which is where he developed a set of tags and conventions that allowed developers to define the data of webpages in a way that machines (instead of humans) could understand. But Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, and dismantled a lot of the research that was going on. So Guha left to work at Netscape.

That’s where he met Tim Bray, one of the creators of XML. Guha began incorporating bits of XML into his own format, and eventually got to RDF. There are lot of technical details that go into formats like XML, RDF and RSS. But what’s really important is what these formats are trying to do. They are unified by a singular vision of a semantic web. The goal being to meaningfully describe the content of webpages in such a way that they can be programmatically connected to other webpages and start to amount to something larger than themselves. It’s hard for me to put it better than Joshua Tauberer:

Take an analogy: the current web is a decentralized platform for distributed presentations, while the SemWeb is a decentralized platform for distributed knowledge.

So that’s what RDF was more or less the culmination of.

At the end of July in 1998, Netscape put RDF to good use. The company launched their new browser portal, My.Netscape which featured a list of syndicated links from popular news and tech outlets for web users to browse through. To pull all this content into one place, Dan Libby took much of the work that was being done on RDF and engineered a parser that could handle it. This took feeds from popular websites, sorted them into sections, and output them to the user.

My.Netscape caught a lot of people’s attention. There were other lists out there of course, but the sheer breadth of content on My.Netscape was impressive. The site gave users the power of choice. And it gave content providers an expanding network of distribution.

People in the web community also took notice, and mostly celebrated the effort. Among them was Dave Winer.

Winer had done some work with Microsoft and XML through his own company, UserLand Software. He was particularly interested in an XML-like format for syndicating blog content, and had even started to work out a format based on work Microsoft was doing, called Open-SPF. When he saw what Netscape had put out, he posted to his blog about creating a standard format for syndicated content. Eventually, he was contacted by developers at Netscape. There were a lot of similarities between SPF and RDF. So Libby kind of merged the two into a derivative known as RDF-SPF, or for short, RSS 0.9.

But some people, Winer included, felt that the RDF influence made things overly complicated for developers trying to create an RSS feed of their content. Besides, it was more like RDF-lite, and if you weren’t going to do it properly, why do it all? So by the middle of 2000, Libby had stripped away basically all RDF influence and put out RSS version 0.91. RSS came to stand for Really Simple Syndication. (By the way, pay attention to these version numbers, they’re going to be important.)

That’s when things started to unravel. It was never settled who technically owned RSS. And at the time, Netscape had been acquired by AOL and had lost a lot of its focus. So the RSS community started to gather in two camps. In one, Winer and developers he had worked with continued to develop RSS as it was with UserLand. Most of the conversations surrounding this development happened on Winer’s own blog.

But another group started to form around a mailing list named the RSS-DEV working group. Members included Guha and a 14-year old Aaron Swartz. The general consensus from this group was that RSS lost a lot of flexibility and extendability when it removed all traces of RDF. By adding some of that back in, RSS could cover a broader set of use cases.

The two groups rarely, if ever, spoke. Which is why in December of 2000, both groups, almost simultaneously, published a brand new version of RSS. The RSS-DEV group produced RSS 1.0 which was much more in the spirit of the original version, with a notable RDF influence rolled back in. A few weeks later, Winer released a quite different RSS 0.92 that added an element to carry audio files (which later was useful for podcasting) but not much else.

From there, the divide only widened. There was a lot of back and forth and in-fighting, but virtually no progress. Starting in 2002, it was proposed by both groups that RSS 2.0 be some sort of compromise, a merging of RSS 0.92 and RSS 1.0.

But that wasn’t meant to be.

The RSS-DEV group more or less split apart. UserLand, and by extension Winer, became the de facto owner of the RSS format. And when RSS 2.0 was finally published at the end of 2002, it mostly just added and cleaned up a few things from RSS 0.92. RDF was once again pushed aside.

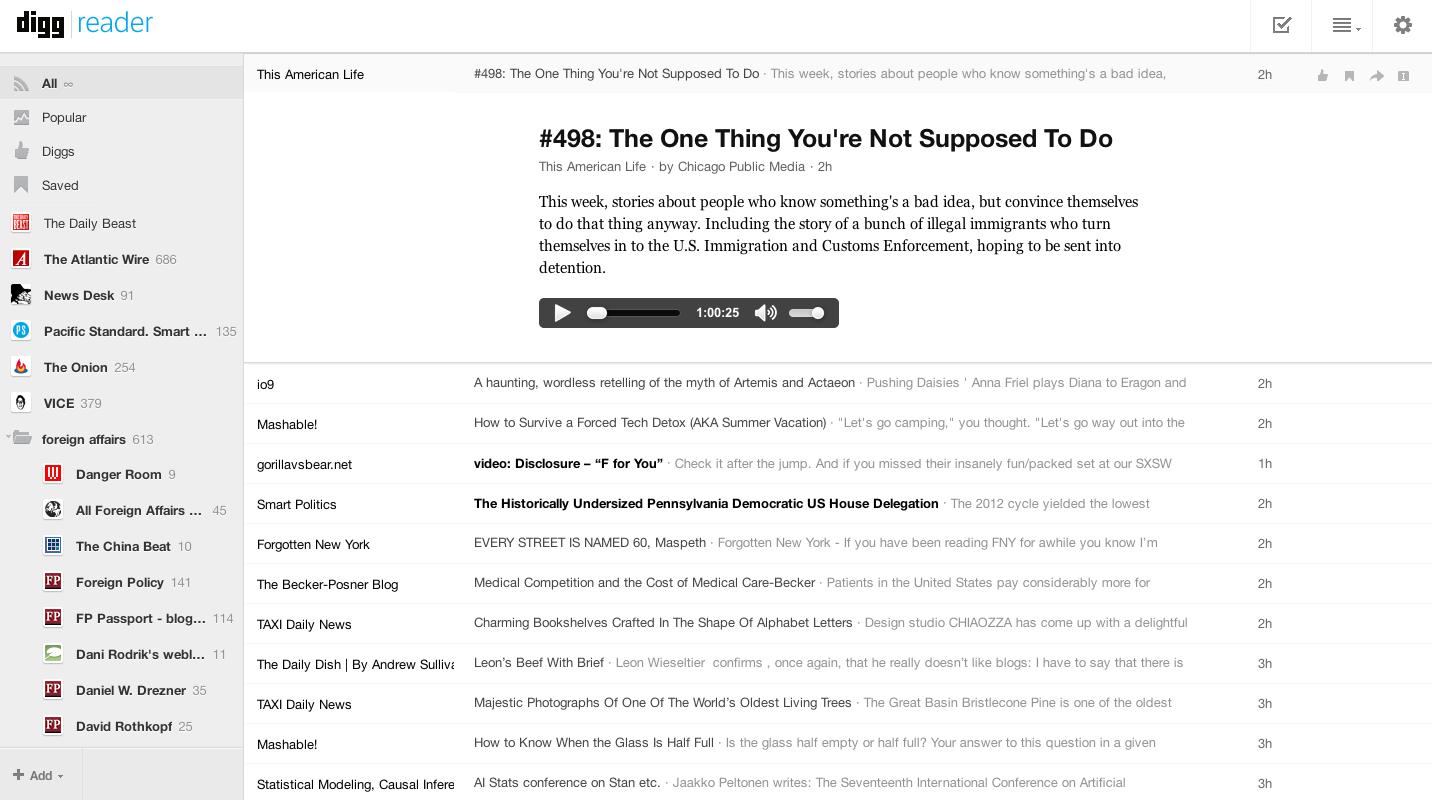

Now it’s probably important to know that amidst all this chaos, RSS was still having its day. Bloggers had coveted this new format right away based almost solely on its promise of a semantic web. But publishers recognized a different potential in the format. The ability to be everywhere. All sorts of applications were being built for users to syndicate content from a variety of sources, and publishers wanted to be there. In November of 2002, The New York Times began syndicating their content using RSS. That acted as a bit of a lightning rod for the publishing industry, and many other publishers came on board.

By the end of 2004, the ubiquitous RSS icon made its way into Mozilla Firefox to designate web feeds. Then, the following year, Apple decided to add podcasts to iTunes. To pull content into their platform, they turned to RSS (already the most popular podcasting format).

![]()

At that point, RSS was pretty much everywhere.

But it wasn’t exactly simple. By 2002, there were seven incompatible versions of RSS to chose from. A large majority picked RSS 2.0, but RSS wasn’t backed by an official standards body, so it was sometimes difficult to get consensus around it. Some even complained that Winer kept too much of the standard in his head.

And that’s what Sam Ruby was stepping into when he proposed that maybe it was time to just start from scratch. Years of tumultuous history had splintered the RSS community into an ever-growing number of factions. To avoid all this, Ruby advocated for a fresh approach, and he was far from the only one to do so. Atom would go through a bunch of names early on (Pie, Echo, Whatever), but its inner workings were clear and considered right from the start.

Atom was discussed in an open, public and centralized wiki so that everyone knew exactly where the conversation was. Conversations split between mailing lists and blog comments had been a huge detriment to RSS.

Atom was imagined as an abstract format and specifically not an extension of existing technologies to avoid the the conflicts in RSS that stemmed from its connection to XML and RDF.

And Atom started with its eye on a small, self-contained community: bloggers. Sure, the format could easily work for publishers and other content creators but starting with the smallest possible subset of content gave the creators of Atom a firm foothold.

Almost right away, Atom garnered a good amount of support from the web community. More than 150 supporters signed up to be a part of the effort in the first few days. Ruby’s post went up in mid-June. By early July a snapshot of the new format was already ready to go.

The final step for Atom was making it as future proof as possible. It was important that no single individual wholly owned the Atom syndication format. After about a year, the creators of Atom brought their new format to the IETF, a third party standards body, to make it an official specification. And sure enough, as of December 2005 Atom was published as IETF RFC 4287.

Today, RSS and Atom exist side by side. You probably don’t even realize this because, though there are some key differences, the formats are somewhat compatible with one another. And most content management systems tuck away the complexity of dealing with both.

Syndication is one of the web’s superpowers. Wiring people to the content they want has always been an underlying goal of the medium. Getting that right was sure to cause some disagreement. What we have today isn’t perfect, but RSS is absolutely a pillar of web technology.

Leave a Reply