There are many ways to connect to the Internet. The web is probably the most common. But in 1991, when the first web browsers were being built and servers outside of CERN were being switched on, the web faced some pretty stiff competition.

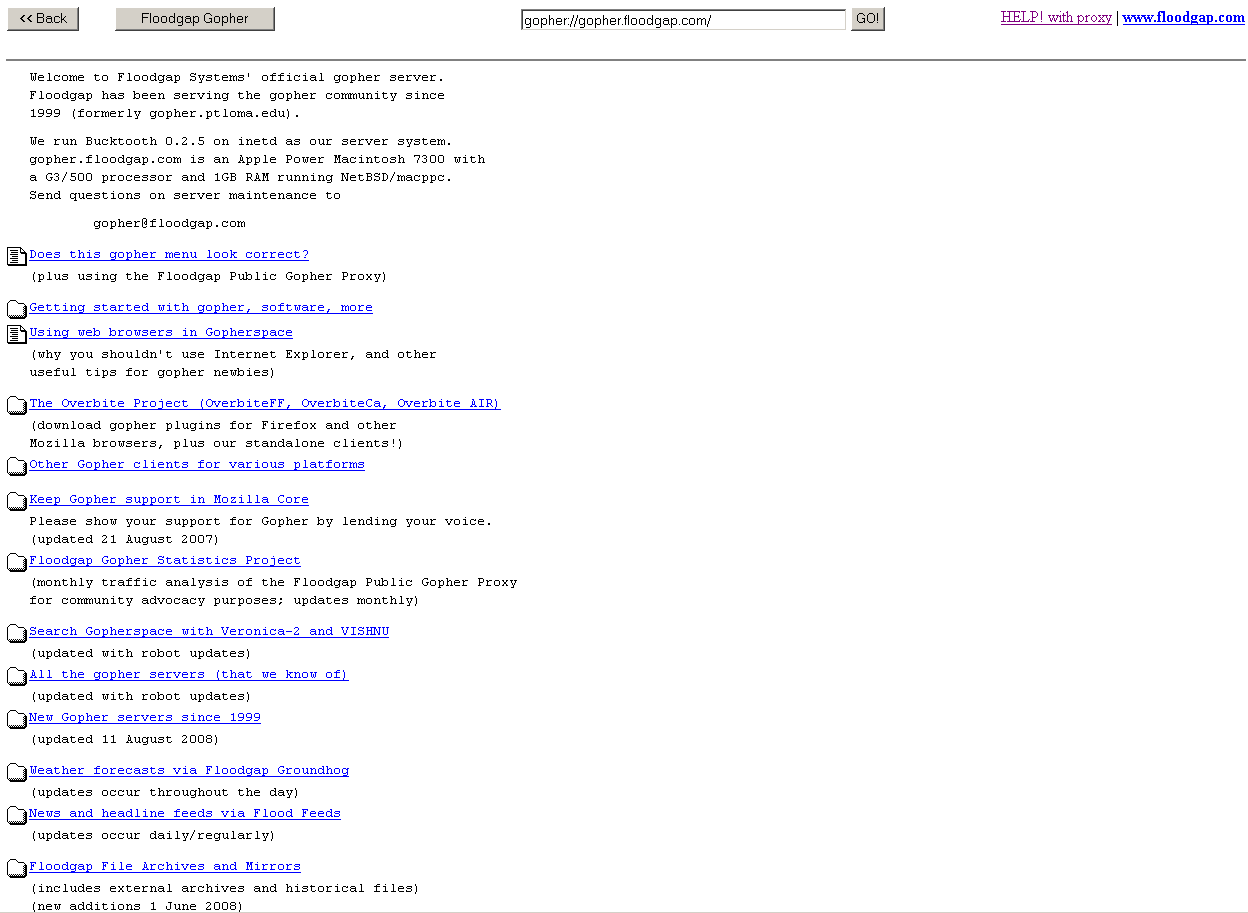

Early in the spring of ‘91, a few researchers at the University of Minnesota introduced a new way of connecting documents on the Internet. They called it Gopher, a pun that included the UMinn mascot and evoked the feeling of burrowing through the Internet. Like the web, what began as a simple protocol soon evolved into an ecosystem that included specialized servers and clients (browsers). Yet, the Gopher protocol emphasized hierarchy over the loose connectivity of the web.

It might be hard to wrap your head around, but Gopher operated quite a bit differently from the web. Any document on a Gopher was assigned, and organized by, a built-in type along with a numerical marker. “0” indicated files, “4” meant an error, “g” was a GIF file, “h” meant HTML, and so on. Gopher clients were used to browse through these files, and bounce from server to server. Typically these browsers would pair file types with iconography to make things more clear. Essentially, users browsed server directories visualized as folders, similar to the way FTP clients work today. Gopher servers could direct users to the type of information they wanted because they were clearly marked and easy to navigate.

It’s easy to forget this, but the Internet was originally conceived as a way to connect (mostly text) documents. So being able to browse documents by type through organized directories was a distinct advantage.

There were other advantages as well. Years before Google, Gopher was solving the problem of text-based search. Separate “search” servers running on Gopher would index and catalog several other other Gopher servers. The most popular of these, named Veronica, could keep tabs on thousands of other Gopher servers at any one time. Most of these search servers were organized by category. As a user, this meant simply connecting to a categorized search server, historical documents for instance, and inputting a query to find the site and document they were looking for.

Pit this against the early days of the web, before CSS and with text only line-mode browsers. HTML allowed for standardized markup sure, but was not nearly as coherent. The web was wide open by design, but this made things hard to find, and sometimes, hard to identify. Hyperlinks could bounce you from page to page or direct you to a dead-end, but Gopher offered a structured alternative.

Gopher did a good job competing. In the early 90’s, it was even the pretty clear winner. By the fall of 1994, there were 4 times as many Gopher servers as there were web servers. It was well liked by its users, and independent technologies like the mentioned Veronica search server had begun to spring up in the ecosystem. So why have you (maybe) never heard of it?

Check back in at the end of 1995, and Gopher had all but disappeared into thin air. There are a few different explanations for Gopher’s dramatic decline. For one, the web had seriously stepped up its game. Web browsers like Mosaic supported inline multimedia with a slick graphical user interface. And as HTML become more advanced, developers were able to introduce visual elements to websites to make them easier to follow. New technologies, like CSS and Javascript, were not far behind.

But the real decline of Gopher can most likely be attributed to a wrong turn made by the University of Minnesota. They begin charging licensing fees for commercial use of the Gopher protocol and servers. Gopher’s creators tried to protest this move, but in the end, they were unsuccessful.

Bottom line, the web was free, and Gopher cost. When corporations and publishers were deciding where to put their resources, they went with free. After that, Gopher’s popularity took a hit. Tim Berners-Lee fought hard at CERN to ensure that the web always remained open. It was a battle he won. Without this decision, we might be talking about the Internet in a very different way today.

We might even be burrowing through a Gopher server.

Leave a Reply