Large, sweeping acquisitions more or less defined AOL’s strategy in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Rapid expansion into networking applications and media production boosted their valuation and inflated their stock price. This all culminated in their grand and public acquisition of Time Warner. This was a company that had been in business far longer with a much wider customer base that nevertheless found themselves in a sale to the relative newcomer AOL for almost 200 billion dollars.

AOL was initially caught off guard by the web, and they spent the first half of the 1990’s trying to head it off. When that became impossible, AOL reversed aggressively in the other direction, buying up companies that could help them expand into the web space quickly. In June of 1995, AOL acquired two more companies, GNN and WebCrawler. A headline from that month sums up their strategy well: AOL buys everyone.

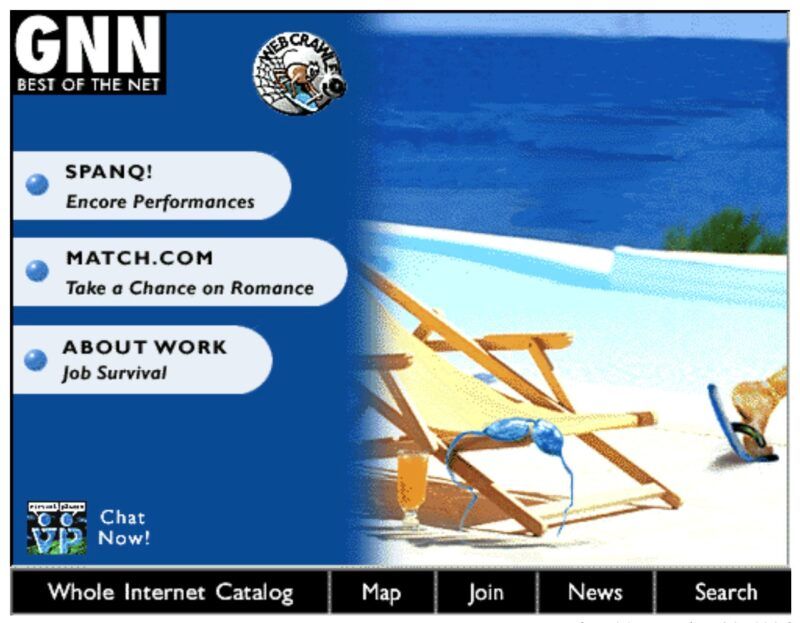

GNN was the first commercial website, and its early entry to the web would make it the first to do many things (first to add graphic design elements to their website, first site with a sponsored link, the first mainstream web portal). It was launched in August of 1993 by O’Reilly Associates co-founder Dale Dougherty, led by O’Reilly’s Lisa Gansky. The team at launch was small, willing to experiment with a new medium.

GNN existed somewhere between a portal and a magazine, offering its visitors a categorized directory of useful websites alongside original editorial content tailored to a web audience. Insofar as it was an experiment by a large publisher, GNN was a massively successful one, becoming one of the early web’s most popular destination. Its acquisition by AOL would double as an expansion of their services, becoming the content arm of AOL’s new entry into the web.

It’s not as easy to trace the first search engine. There were several different websites that attempted to index the web’s information. Among those, if not the very first, was WebCrawler. Developed by Brian Pinkerton while he was still a CS student at the University of Washington, WebCrawler first launched in 1994.

Its greatest distinction was that it was the first to crawl the full text of pages. Other search engines relied on titles or other metadata for search. WebCrawler made it possible to search for any text on any webpage. It was seeded with some 4,000 webpages when it was first released, but it would soon have many thousands more.

By the time the search engine was bought by AOL in 1995, there were several other entries to the market, including the much-hyped Excite. Still, AOL believed that in order to provide a full web experience for their customers, they would need to pair it with a strong discovery and navigation experience. WebCrawler was meant to be part of that.

AOL had a habit of smashing together companies when they could, which is exactly what happened with this round of acquisitions. WebCrawler was folder under the GNN brand, and they were collectively expanded into a complete web package for subscribers that wanted full Internet access. For $14.95 a month, GNN subscribers could browse the web for up to 20 hours (it was $1.95 an hour after that). The GNN website and WebCrawler became the service’s front door, their way to engage with the latest and greatest content of the web. It was also around that time that WebCrawler got its first official mascot, Spidey.

GNN began looking for ways to promote their new mashed together super-brand. Lisa Gansky and Jim Gustke from GNN found what they were looking for in Seth Godin, who was beginning to grow a business around an idea he has called permission marketing. In Godin’s view, customers are willing to give their permission to be marketed to, so long as they are given something valuable in return. And a customer that has given their permission is far more engaged — and much more likely to make a purchase — than one who has not. The Internet, he argued, was the perfect venue for permission marketing. It allowed direct relationships with customers with little friction, particularly through web communities and email.

Godin had just recently staked his career on permission marketing. His marketing firm, Yoyodyne, was built on its premise. Yoyodyne had partnered with several companies to create large Internet-based sweepstakes and giveaways. Visitors would sign up for a newsletter list, or fill out a marketing survey, for a chance to win a prize. It was a simplistic version of permission marketing, but one that had helped Godin grow engaged customer base for quite a few large brands. AOL wanted to do something like that. But in typical AOL fashion, they wanted to do it bigger.

GNN wanted to showcase their new portal as a dynamic and engaging way to surf the web, simultaneously showcasing some of their content partners, many of which were other AOL acquisitions. Working with Yoyodyne, GNN put forms on a dozen or so partner websites, such as Match.com, Netscape, and Parent Soup. Each form would give its visitor an entry to the contest. Finding them was a web-based scavenger hunt, guided by GNN and WebCrawler, that led to a bunch of sites AOL thought were important. The more forms filled out, the more chances to win.

The prize: a million dollars. Not surprisingly, it was called the Million Dollar WebCrawl. Short, and to the point.

Nothing had ever come even remotely close to that type of money online. It wasn’t niche web audience money. It was mainstream swing for the fences money. And it was a huge success. GNN got 350,000 emails. People visited partner websites to sign up millions of times. It was covered in the press, and shared among nascent internet communities and mailing lists. And it launched Yoyodyne to a new profile entirely.

The winner was a fork-lift driver from Pennsylvania. For all the entrants that had spent their time surfing from site to site to collect entries, the winner only signed up once. It was on Match.com.

Even after its success, GNN didn’t last much longer. AOL got distracted with something new, and began to focus elsewhere. They were a volatile brand, and this would be nothing new. After 12 months, GNN was shut down, and Internet access was opened up to all AOL subscribers for the now well known $19.95 / month for unlimited access.

This tactic, one of million dollar giveaways, would become more common over time. And as Godin has pointed out, each time one happens, it becomes a little less novel, and a little less effective. But to get swept up right there at the beginning. To get a chance to win a million dollars just by visiting some websites. That felt a bit magical. And it signaled a much different web that was jut around the corner.

Leave a Reply