This post starts with a book. This book:

It’s called Jargon: An Informal Dictionary of Computer Terms. That’s my copy. It’s a book I stumbled on while researching this topic, and one I’ve come to truly love for a variety of reasons, not the least of which because it’s written by Robin Williams who may but almost certainly isn’t the Robin Williams (the writer, herself a prolific author, has an extremely entertaining FAQ about the salient differences). There is, of course, also that fantastic book cover, which features an almost abstract painting representing the confused look that’s crossed everyone’s faces from time to time trying to figure out what the heck somebody is talking about on the Internet. But really, what I like most about the book is the way that it talks about those hard to understand abbreviations and computer-only words that it refers to as jargon. The scope of the book is in no way limited to the web, or even the Internet, but Internet jargon, or Internet slang as its sometimes called, takes up a good amount.

In the beginning, the web was just text. Over the years, we’ve added plenty of video streaming, and there’s quite a few images (mostly GIFs) floating around. But the web is still, essentially, text. The way people talk online is constantly evolving but it has always, at best, been quite different from the way we talk in the real world. Over the years, a shorthand has developed which incorporates not only an ever-growing list of hard to follow abbreviations but various mixed and remixed memes, in-crowd references and inside jokes.

There are plenty who decry this form of communication as the death of all that is good and decent in casual conversation. However, this blanket generalization ignores the nuance of the modern day and the potential advantages that Internet slang brings with it. Some researchers and academics have even adapted studies of technology and linguistics to try and understand it.

David Crystal, for instance, has been a pioneer in the field of Internet linguistics. Crystal argues that an online conversation, be they in a private or public channel, is more like a face to face conversation than it is like formal written communication. This seems rather obvious when you say it out loud, but it is theoretically counterintuitive. When we write to each other online, especially on chat and social media platforms, we mimic the way that we say things instead of the way we would typically write. Crystal even points to the fact that there are variations, colloquialisms, commonly used phrases, or dialects, that can be found as you move from one online community to the next.

As a way of substituting the visual cues of face to face interactions, users online inject a bit of playfulness into their conversations. A reference to a movie, or a remixed meme, or a grammatically incorrect affirmation (because the Internet) lace the conversations online with a bit of subtext. There is the thing we’re saying, but a lot of online communications acts as a kind of test. If you “get” the reference, you can be on the inside of the conversation. Crystal sums it up like this:

The chief use of slang is to show that you’re one of the gang.

Researcher danah boyd has a different take on the abbreviations and obscure phrases used by teenagers in online communication. In a paper published in 2011, one that is still extraordinary relevant today, boyd and fellow researcher Alice Marwick described a technique known as social stenography, the practice of obscuring the meaning of private information in public spaces through the use of veiled references and cloaked abbreviations, typically deployed by teens on social media platforms. Those savvy enough to be active on the web implicitly understand that their privacy online is compromised and has been for some time now. To cope, social stenography makes it hard for people outside of a group to understand what’s being said. A conversation might look like it’s saying one thing, but it’s buried beneath so much sarcasm and obtuse phrases that it can be hard to understand, keeping the truth away from prying eyes, even in full view of everyone.

In recent years, it feels as if we have reached a new plateau. One only needs to look at at a typical Snapchat exchange or Twitter thread to see the way text and images, abbreviations and memes, swirl together in a sort of performative irony. Understanding the true meaning of these conversations requires a context and familiarity with Internet speech, not just the text patterns or mode of speech, but whatever the conversation is referencing, be it a meme from a movie or a subtweet of some other conversation.

Even the baseline can be hard, dissecting the meanings of various abbreviations and Internet slang. New phrases are added to the lexicon every day. Some stick around. Others vanish without a trace. The FBI even maintains an active list of slang for use in its investigations. It can all get a bit confusing. And abbreviations can be among the hardest to track.

Which brings me back to Jargon.

Jargon does not, as other researchers have, presume to know why these words and acronyms exist. It is a glossary, as comprehensive of one as you could hope to have when it was first published in 1993. Its job is to uncover the meaning behind jargon. To make plain for readers what is otherwise almost impossible to parse. To present, in clear language with a dash of humor, both definition and context simultaneously, both text and subtext. At this, it does an excellent job.

For instance, the book has this to say about imho:

The little acronym, imho, stands for in my humble opinion. It’s often used as a typing shortcut in online communication. When it is capitalized, you are shouting.

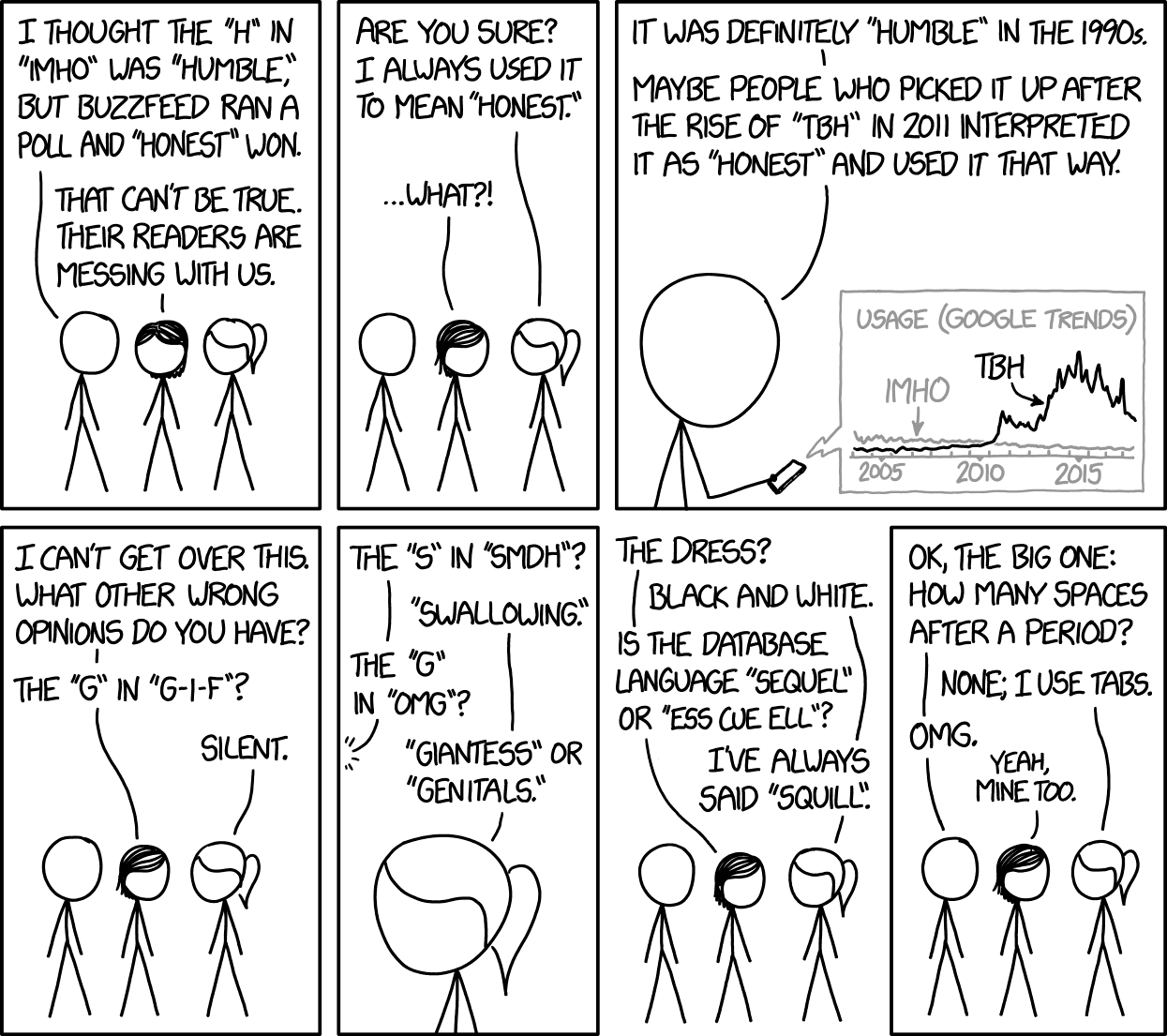

IMHO got its start in either PC Magazine or on the short-lived television drama My So Called Life. It’s a bit hard to trace. And depending on who you ask, it stands for either “in my honest opinion” (wrong) or “in my humble opinion” (correct, and the book backs me up), and has been the subject of much debate recently. It is one of those words that really only makes sense online. A way of deflecting blame for your own opinion while expressing something that may be unpopular.

IRL (In Real Life) stretches back to the early days of the Internet. But the phrase itself didn’t really take off until the website of Jurann Foxtail, an artist, writer and furry fandom aficionado made reference to a cartoon animal as being extraordinarily close to his real likeness.”It even looks like me IRL”. Since then, me IRL, has taken on a life of its own and become a way to digitally wink at our online persona. It implies that the online world is somehow distinct from the real world. Jargon, interestingly, has an entry on the Real World:

The Real World is a vague where they tell us Life happens. It’s where teachers and parents always threaten us of things that are different and someday we will find out and be taught Great Lessons. Where is the Real World, I wonder? I’m hoping to avoid it.

New abbreviations sometimes appear out of thin air. Jargon doesn’t mention TL;DR (too long; didn’t read), because it didn’t hit the mainstream until well after the book was published. It’s one of the only Internet slang terms that actually originated on the web, likely in the Something Awful forums in the early 2000’s, as a way of indicating a short summary of something much longer. It’s one of those terms that, just because you know what it stands for, doesn’t mean you know what it means. And it only ever makes sense on the web, where long online discussions or diatribes demand too much of our split attention spans.

I guess what interests me about Jargon is that it sets about trying to index the entire lexicon of computer jargon at all. That its author found that to be an attainable project. Because even in 1993, the list was extremely long and hard to understand and the task set in front of the author was a daunting one. We can try to understand why we talk the way we do online, but before we can do that, we have to know what it all means to begin with. The book provides an excellent first step which has been extended, to some extent in spirit, by sites like Know Your Meme and Urban Dictionary.

Even with crowd sourced content, it would be impossible to take all of the weird phrases and abbreviations that we use just in our everyday life, and cram it into a single book. But it sure is fun to remember a time when you could.

Leave a Reply