I’ve been digging into the history of search engines and centralized platforms lately. Mostly my goal has been to uncover what happened on the web to make privacy a commodity that is less than sacred, and intensive advertising the dominant business model. It’s easy to think that our current modus operandi (tracking scripts that follow us everywhere we go) starts with, and more importantly was perfected by, Google. That they were the ones that invented the advertising marketplace and introduced precise targeted advertising. What I’ve discovered is, that is not at all the case. That particular distinction rests on the shoulders of the little-known precursor to Google. A search engine that first went by Goto.

Goto launched in 1997, conceived and developed at Idealabs, a Pasadena-based incubator that over the years has been responsible for companies like NetZero, Picassa, and Answers.com. Idealabs was run by Bill Gross, who was particularly interested in how to improve search on the web.

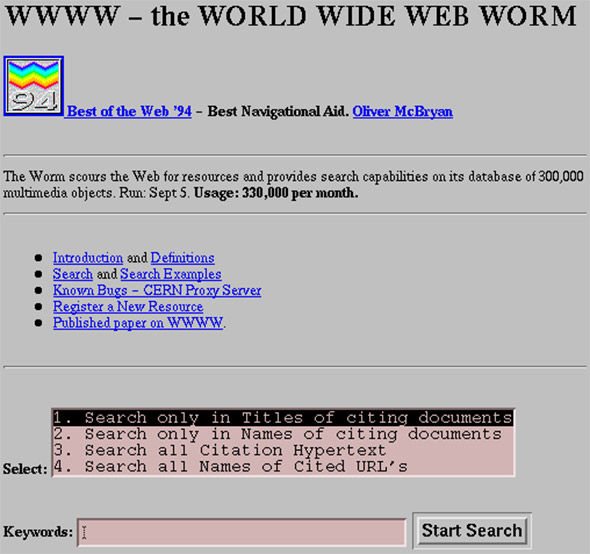

He started by buying up World Wide Web Worm (WWWW) which was, incidentally, one of the web’s first ever search engines. Gross thought if he could give the site a new coat of paint, and maybe tweak the user experience a bit, he might have himself a search engine that could rival the major players of the time.

Gross and his team latched on to a single idea. Focus on search. Big names like Lycos and Excite had begun diluting their search experience, surrounding it with more and more cruft. Things like free mail and editorial content and link lists made it sometimes hard to fine where the search bar even was. The new and improved WWWW got rid of all of that and left only a focused, solitary search field smack in the middle of the page (a little while later, Google would cop the same look).

This new direction would need a new name. To live up to its straightforward design, the team went with Goto.com. But Gross wasn’t done yet. Far from it. He had another idea and that would require a bit of finesse and tenacity and in what turned out to be a rather bold move, he decided to unveil his new idea to the audience at the TED8 conference in February of 1998.

Shaking Things Up at TED

TED talks are usually the scene of unrelenting optimism and inspiration. But the audience gathered in the hallway after Gross’ talk that February was more confused than anything else. Some were even a bit angry.

Gross went up on stage and pitched his idea for a new kind of search engine to the conference-goers. It would work like a lot of other search engines out there. You type in a few words and get back some results. The big difference though (and it’s a big one) was that all of the results on Goto, every single one of them, would be powered and populated entirely by advertising. Advertisers would be able to purchase sponsored results for whatever keywords they wanted, and those sponsored results would be the only ones shown to users visiting the search engine.

With advertising literally everywhere these days, this might feel almost commonplace, but it was truly radical at the time. Technologists building search engines were still mostly purists who viewed ads as only a necessary evil and a reversal of the ideals of the web. About six months after Gross got on the stage, Google would launch to the world. Its founders, from day one, would be adamant that they would never, ever allow advertising to dictate their business model (we see how well that turned out). Even before Goto, another search engine by the name of OpenText was largely relegated to the annals of forgotten websites after its users found out that there were sponsored results mixed in with organic ones.

So even having a few advertised results at the time was a little bit crazy. But being way out in the open about it, making it a selling point like Gross was proposing. That was downright abhorrent.

Gross saw all of this as foolish blindness. To his mind, search engines had already been compromised and not just by advertising, but by something worse. Spammers had begun to invade the web, filling up pages with overused keywords to trick search engines into giving them a top result. And it was working. Gross figured he’d flip the script. By making every result on his search engine paid for by advertisers, he could let the marketplace do the work of filtering out bad results from good one’s. Spam wouldn’t be a problem because spammers wouldn’t pay.

Goto even built out a new marketplace for results. Advertisers could visit this online marketplace and bid against one another for higher placement under certain search keywords. Each result started at exactly 1 cent, but the hope was that over time, valuable keywords (think: “buying a car” or “television”) would be worth far more than that. To make the deal even more enticing, Goto also promised that advertisers would only have to pay up when a user actually clicked a link, not just when they saw it. So if you’re wondering, that’s where pay-per-click came from.

You have to admit, it does make some kind of sense. It’s no different from the way, say, the Yellow Pages work. Which is the line Goto often touted when asked about their business model. Not to mention, they went out of their way to let visitors know that each result on the page was sponsored. It was all meant to be out there in the open. There was nothing clandestine about their operation.

Well, except for how they got clicks.

Gathering Steam

As the new search engine on the block, Goto needed a way to attract people to their search engine so they could see the sponsored results. So Gross came up with a shell game to get users where they needed to be. He would go to another content portal, like Yahoo or AOL, and buy results on their pages for something like 4 cents a click. Those visitors would be directed to a similar page on Goto, where they would be given a list of advertised results. So as long as the value of each user that clicked through was higher than that initial 4 cents, Goto would make some money.

They didn’t make money. Not in the beginning. But Gross gambled that overtime, because of Goto’s bidding model, these sponsored results would be worth more. And he was right.

While the rest of the web spent a lot of time mocking its business model, Goto actually did manage to become incredibly profitable. By mid-1998 they had backfilled a lot of their content with organic results powered by a third party service known as Inktomi, a company that specialized in that kind of thing. That made the results for each keyword, especially those without a lot of sponsored results, way more relevant. Organic traffic led to more visitors and more visitors eventually led to an incredibly successful IPO IPO in the summer of 1999, bringing in tens of millions of dollars in funding almost instantly.

Becoming Overture

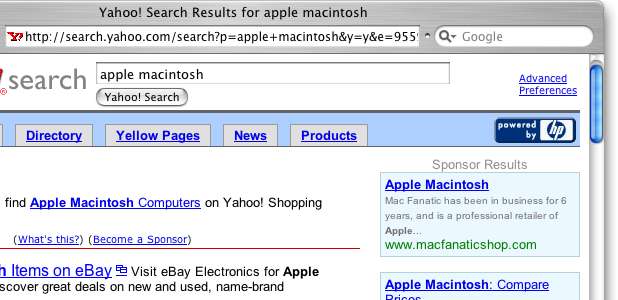

That’s when Goto began exploring a different direction. Instead of trying to bring users directly to their own site, they syndicated their results to other search engines and content platforms. So sites like AOL or Excite or Yahoo would include some links from Goto. If users clicked through, some of the money from the click would go to the platform, and some to Goto. This actually wound up being particularly lucrative. It removed the need for Gross’ shell game and let massive platforms do the heavy lifting of bringing users in.

Gross, and a good amount of the team at Goto, didn’t agree. They wanted to see their site become a destination in its own right.They didn’t want to compete with Google. They wanted to become Google. But pressure from investors, and their partners, eventually refocused the entire business around the syndication model, more or less getting rid of the main site altogether. In 1999, not long after the IPO, they changed their name to Overture and concentrated entirely on boosting their syndicated traffic with high stakes partners, acting as a sort of middleman between advertisers and search engines.

Over the next few years they would continue to grow. They even began gobbling up other search engines, acquiring both Alta Vista and AllTheWeb in 2003. And the money just kept coming in, as advertisers raced to outbid one another for the most popular search results.

At some point, Yahoo realized that over 20% (that’s right, a fifth) of their revenue was actually coming from their partnership with Overture. And that’s just revenue. Since a lot of the services built into Yahoo were in the business of losing money, the company’s share of their profits was even higher than that. They did the logical thing. They acquired Overtue for over a billion dollars in 2003.

And as sometimes happened when Yahoo acquires you, the platform eventually faded away. That however, is part of a much larger story about search on the web.

Goto is one of those hidden origins on the web. It’s a site that was never truly beloved by the public, or lauded by evangelists or the press. And yet with very little fanfare it had a massive influence on the growth and development of search engines on the web. For better or worse, Goto was the first modern search engine.

Leave a Reply