The fan fiction community is tough. Resilient. Fandom — a catch-all term that includes fan fiction writers, readers, and participants at various levels — is more than stories featuring characters and situations plucked from pop culture. It’s a dynamic and evolving culture with a decades-long history that started out in the real world, but grew up on the Internet.

The culture itself is by its nature anti-hegemonic; it does, after all, incorporate copyrighted material without express consent, and its sub-genres like slash fiction deal in sensitive material. And yet this burst of creative expression is deeply important to lots of people on the Internet. It is, for instance, one of only a small number of relatively safe space for women, who make up the majority of fandom. And the content may be explicit, but the meaning in fan fiction is almost never banal. These stories are filled with subtextual and explicit links to philosophy, particularly feminist and queer theory.

Because the material of these stories is overly sexualized and because it deals in copyrighted material and because the community is represented broadly by individuals from marginalized groups, and because of a dozen other reasons, they have learned to be adaptable. They have to be. Fandom is constantly forced off the platforms they chose to publish their stories on.

I’ll give you an example.

May 29, 2007 is known as Strikethrough ’07 among fans. It’s the day LiveJournal decided to ban dozens of fan journals and blogs in a single moment. The banned users were marked on the site with a simple strikethrough. That’s how it gets its name.

LiveJournal was targeting users with specific interests. The move was intentionally malicious, the interests banned from LiveJournal were being used to distribute illicit and unlawful content. The execution of the ban, however, lacked nuance. In an act of blanket censorship, LiveJournal made the decision to automatically suspend accounts based on tags used in their “interests” section, tags such as incest and rape. Because this rule was applied broadly and indiscriminately, it included entirely legitimate users of survivor communities that used these tags to find others that had lived through the same kind of trauma that they had. It also included a large cross-section of the fanfic community that used these tags to group and categorize their entirely fictional, erotic, pop-culture inspired stories.

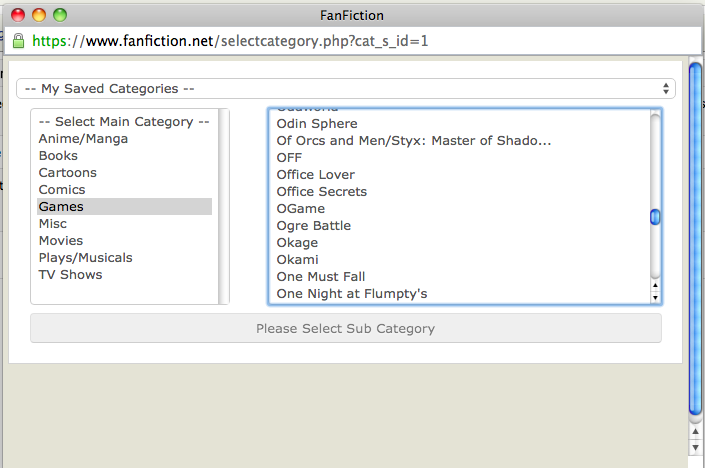

This wasn’t the only time this had happened. The fanfic community, with its flair for the dramatic, has its own theatrical way of retelling the events that have shaken the community out of one platform to the next (most of them are absolutely worth reading if you have the time). FanFiction.net, a popular alternative to LiveJournal, has banned various content at different times since 2002. Tumblr has disrupted the fanfiction community several times, most recently in 2018.

Every time a ban like this happens, scores of fans pick up their content and move to another site. To help with the problems of large-scale migrations, fandom has produced a number of written and unwritten rules that members are expected to adhere to. These rules better the community. They make content more findable. The rules are distributed through word of mouth, in blog posts, wikis, and comment threads. There are more than a few getting started guides, and some senior members of fandom help out the newbies. Sticking to a loose set of conventions has kept fanfiction resilient. And a lot of these rules deal with tags.

Tags

Tagging seems simple and straightforward. It’s not. Without a higher order hierarchy as a baseline, each person has a different approach.

Imagine you went on a trip to the Grand Canyon with your family. You come home with dozens of photos that you upload to some app. The app lets you add tags, so you go through and add some. Some of the tags you add are for purely categorical reasons. They’ll help you find that photo later. You’ll likely stick to a rigid glossary of terms you didn’t even know you were pulling from. For instance, you’ll probably put the location of your trip, Grand Canyon, or the year. Maybe you’ll include the name of some of the specific stops you took. You might even pull in some related concepts, like the highway you took there (I40) or that animal you kept seeing (Bighorn Sheep).

But then you might get creative with a few. Maybe your dad wore the same Fedora the whole trip and wouldn’t take it off so you give any photo with him in it the tag FedoraDad. Or maybe you met someone you thought had a connection with, only to lose their info. Any of these pictures would get the tag MissedConnection — or if you’re feeling dramatic — LostLove. A good amount of tags you use would be a collection of personal references, inside jokes, and narrative additives. These tags do nothing for the actual organization of your photos. They don’t classify the content — by the act of tagging, you add new meaning to what’s being tagged.

Folksonomy

On the web, this kind of freeform tagging is known as a folksonomy, a portmanteau of folk and taxonomy. The term was coined by information architect Thomas Vander Wal in a blog post in 2004, but as a concept, it had existed for several years already.

Folksonomies are generally non-hiearchical — completely open-ended. In a folksonomy, you can tag something anything, even if it’s disingenuous, absurd, or entirely unique. That’s what’s meant by freeform. In practice, tags inside of web interfaces are often suggested based on what you’ve used before to maintain some sort of commonality between them.

The first folksonomies existed for individuals, on platforms like Flickr or Delicious. Think Gmail labels, where you structure your tag system based on personal preference, and the autocomplete in the tag field help you discover terms you’ve used before.

Tags on the web, incidentally, were created by Delicious founder Joshua Schachter, who had been using them for years to organize files on his own computer. He actually prefixed all of the tags he used on his computer with a # symbol to make them easier to find later. By the time he got around to building Delicious, he had figured out a way to drop the# and make tagging simpler. A few years later, Chris Messina would pick up on a similar idea, adding the pound symbol back in, when he suggested what would eventually become the hashtag at Twitter.

There was a second wave of folksonomies that weren’t personal; that were meant for everyone. Tags acted as a “reverse search engine,” a way for users to find content based on their interests. Platforms like Stack Overflow, later iterations of Delicious, and the Twitter hashtag, are great examples of this. In this type of folksonomy, tag structures tend to follow from discoverability instead of entirely from personal preference, and tags suggested by autocomplete are sourced from popular search terms, not necessarily tags that you personally have used before.

Folksonomies are not without their problems. How does one, for instance, prevent a system where each tag is entirely unique and unfindable. What about misspellings? Or synonyms? Or words that have different meanings in different cultural contexts? And of course, even if you were able to smooth all of those issues, and dozens more, out, there’s still not a great way to incorporate the personal tags that enhance rather than categorize the content. How do we, in other words, account for #FedoraDad?

Fanfic and Tags

Tags have been used in fanfic for the duration — even before the Internet — when fanficiton stories lived in narrowly distributed print zines. The term slash, a fanfiction genre that deals in homosexual erotic pairings of popular characters, a genre which kicked off fandom, was one of the earliest and most widely circulated examples of a fanfic tag. In fact, slash gets its name from its tagging convention; a slash story is indicated by two characters joined by a slash symbol, as in Kirk / Spock.

Over the years, fandom classifications transformed into a sprawling index of written and unwritten rules. Using the same word of mouth networks they had always used, the beginner guide and mailing lists, and community trendsetters, these tags where disseminated and refined. There were big all-encompassing categories like Slash and PWP (Plot, What Plot?). But there were also a number of hiearchical and categorical groups to select from. Tags for characters (Magneto, Kirk), genre (Action/Adventure), relationships (M/F, F/F), kinks (BDSM, Multiple Partners), and a lot more.

These categories, however, were self-enforced. Platforms like LiveJournal allowed for freeform folksonomies — users could add any tags they liked whether or not they fit into pre-existing vocabularies or not — but without an easy way to pull from a pre-approved list. A notable exception to freeform tagging wason the website Fanfiction.net, which let users assign tags to a number of pre-baked categories (Character, Relationship), but left out freeform tagging.

Not to be deterred, some fastidious fans took to bookmarking sites like Delicious or Pinboard to collect and tag fanfic stories in one central location. That was hard to trust in the long run. In 2011, a redesign to Delicious obliterated its tagging features and made it almost unusable to fandom (a saga which is the subject of an incredible conference talk and produced a mind-blowing Google Doc).

An Archive of Our Own

In a prescient post on her LiveJournal, fanfiction writer Astrolat warned fellow writers that sites like LiveJournal and FanFiction were not to be trusted. She was particularly concerned with a new website called Fanlib that some fans had discovered, on close examination, was trying to claim ownership of the stories published on their site. From the other side, authors had to deal with rampant and random censorship whenever a website decided it was time to crack down on sexually explicit content. Astrolat proposed an alternative. A website built by fans, for fans, and supported by fans.

The timing of her post was uncanny. Strikethrough ’07 — LiveJournal’s censoring of popular fanfiction blogs — was just a few weeks away. By then, Astrolat’s alternative was underway.

Fandom took to this new project with their usual verve and meticulousness. While the dust was still settling on Strikethrough, members of the community — some of them professors, librarians and software engineers — had already created a non-profit to support the website. Soon they had volunteers to help build the site. They sub-divided into a number of committees, each run independently and responsible for a different area of the site (for instance, the Systems Committee and the Content Policy committee). Within a year, they had themselves a website. They named it Archive of Our Own (AO3 for short).

There were several things that set AO3 apart. It is backed by a non-profit and run by fans. There is no advertising. It doesn’t require your real name. There is no reason to censor content, the site even has a mandate not to. Its first priority is its users, and it strives to maintain a safe space for authors and readers with strict policies but open content guidelines.

But one of AO3’s most striking features is its tagging. The site’s creators came up with a tagging system that is unlike anything else on the web.

Curated Folksonomy

The first feature of AO3 tagging is that it’s incredibly open. Users can group tags in a number of categories, and are free to enter whatever tags they want for a post.

Here’s a slash about Doctor Strange and Iron Man. It has the tags you might expect, i.e. Tony Stark / Doctor Strange and Marvel Cinematic Universe. But it also has a few extras thrown in for some context, such as A teensy bit of angst in the beginning or its Stephen being a hot mess.

That accounts for #FedoraDad. AO3, however, goes one step further using a methodology that Professor Julia Bullard at the University of British Columbia has called a curated folksonomy Bullard has conducted a long-term ethnographic study of curated folksonmies on the web. What she, and others, have found is that though they require significant effort, they make content infinitely more findable.

To bring a sortable, overarching structure to tags, AO3 created a volunteer group of individuals known as Tag Wranglers. The job of the Tag Wrangler is to try to find balance and even out the inconsistencies between tags. They fix misspellings, they combine synonyms, they make sure that tag groups remain meaningful. But a Tag Wrangler only seeks to better organize content so it can be found easier by fans. Creative asides, absurd misnomers, or personal references are actively left alone. Listen to how one Tag Wrangler describes their job:

The Ao3 Terms and Conditions and the Wrangling First Principles both strictly prevent us from being gatekeepery. We can’t change tags, we can’t tell users how to tag in any official capacity (“describe not proscribe”). Our goal is to organize tags in a way that fans will be able to find what they’re looking for. To do that, we have to speak their language and use the words they use.

The Tag wrangler position is considered sacred. They preserve the platform by finding meaning in tags and bringing it out. They do not, under any circumstance, bring their own meaning to it. They are there to boost the work of theres. The committee meets regularly to discuss updates. When they overstep, the community is ready to meet them.

It is only with that level of dedication and care that fandom has managed to stay whole. They can protect their users while still promoting their stories. They are community unlike any other on the web. And they have perfected the folksonomy.