In an interview for her book Internet Art in 2004, writer Rachel Greene had this to say about why she felt the subject of her book was so important:

I refuse to let commercial interests dominate the history and perception of the net because I think they would exclude the most important and dynamic internal content – the aesthetic, creative, radical, political ideas and experiments that I describe in Internet Art.

The subject of Greene’s book was the pioneers of early Internet and web-based art, a wide and sprawling subculture united under a flag of incredibly loose but still somewhat common themes, motifs, and techniques. Like many art movements, especially those in the post-modernist turn of the information age, it was a bit hard to define. But at the core of the book was a look at the collective net.art, a group formed at precise moment of time on the web in the mid-90’s. The book was not simply an homage to the work of net artists, it was an attempt to collect the pieces of that culture before they blew away like so much dust.

net.art is likely familiar for many of you, especially those who were users of the earliest iterations of the web (though maybe it’s not something you’ve thought of in quite a while). For me, it was something entirely new. A corner of the web that’s receded to the edges of history.

On this blog, I mostly deal with stories about the web told with at much objectivity as possible (though I will admit I am prone to a subjective impulse now and again). This post is a bit different. It’s as much a history of net.art as it is the story of my personal excavation of the material. Unlike much of the subject matter I deal with, this was something I had never come across. It’s rare that I turn over a stone on some forgotten isle of the web and find myself absolutely floored by what’s underneath. I was with net.art. So this is simply an attempt to share that wonderment with all of you.

The history of net.art is as amorphous as it is hard to pin down. Certainly, experiments with the web medium as a means of artistic expression began almost as early as the web itself. But our focus is on a thinner band of that history that began in the nettime mailing list, created by Pit Schultz and Geert Lovnik in 1995. It is through that mailing list that a sort of collective began to form, a group of artists that were fascinated with the web medium and sought to experiment with and explore its boundaries.

In fact, the nettime moniker was an intentional choice, and ran counter to the futuristic otherworldly names the Internet was given at the time, names like cyberspace or information superhighway. Nettime was a nod to the social context of the web, that users of the web existed in time, alongside one another. Net artists were among the first to recognize that our online world and the “real world” are, in fact, the same world.

Which is what initially drew me in. As a card-carrying member of a group of individuals the media likes to call “digital natives,” my true identity was shaped and formed on the web. I made my very first web site in high school, and that site’s creation is what ultimately endeared me to a small circle of friends and gave me some sort of outside purpose. And that’s before I started making friends on the web, talking to others just like me for the very first time. It was an incredibly transformative experience that is entirely unoriginal and likely shared by many of you. But it’s important, because here’s a group of dedicated artists that formed in much the same way, by poking and prodding the web and sharing what they found as they found it.

There is not one thing that defines a net artist, and I think you’ll find that their work is as varied as the personalities of its creators. Their connection, therefore, is grounded in a shared understanding of the possibilities of the Internet. These were a group of individuals who saw the web not as a means of utility, say purchasing something or reading an article, but as a means of collaborative expression created by the artist and experienced by the visitor. They were the web’s rogue avant garde movement, set apart from both from the wider web world, where the focus increasingly moved towards business interests and commercialization, and the mainstream art world which overlooked them for years. And in that middle-ground reality, they created brilliant works of art.

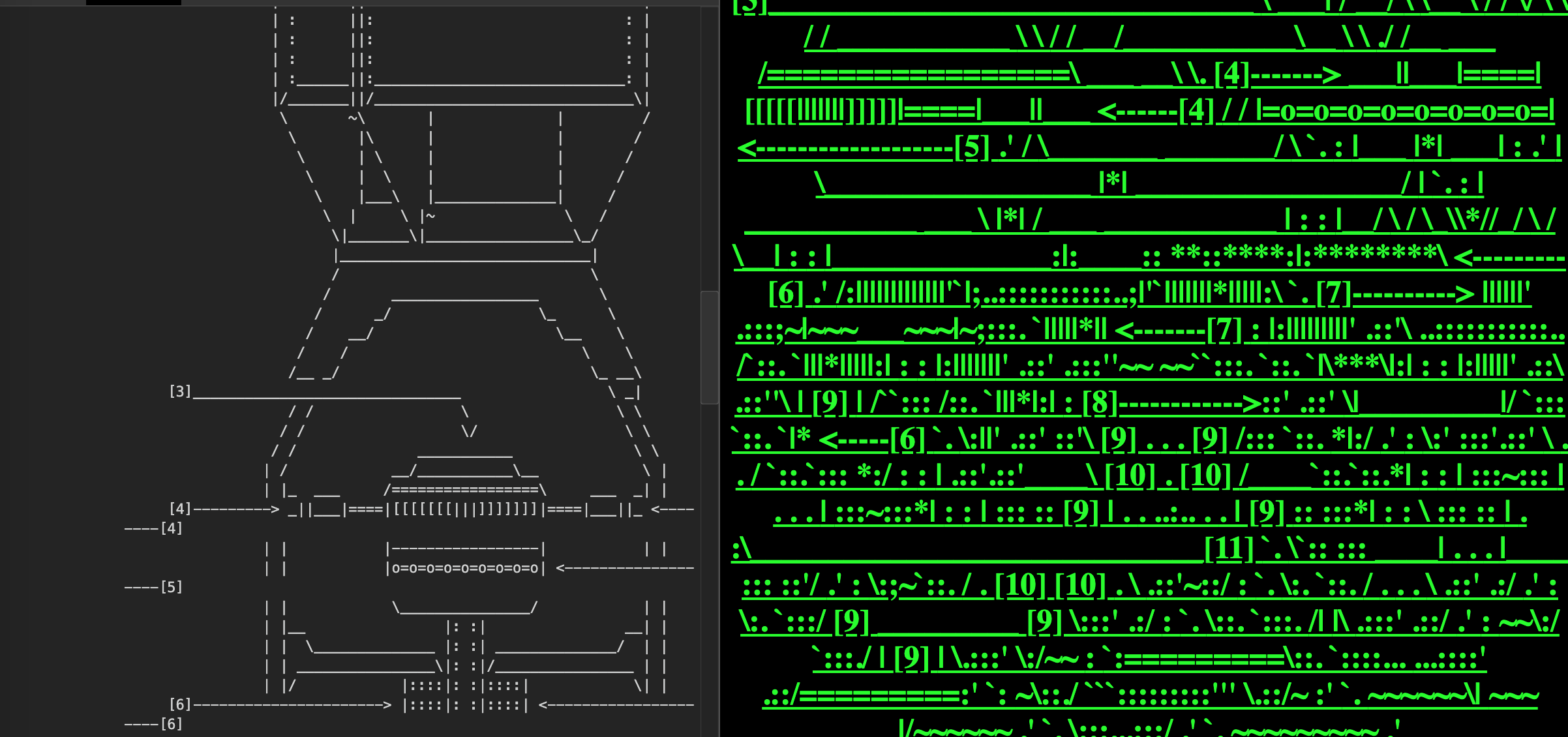

There was the collective JODI, made up of Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans, that quickly gained a reputation for playful and counterintuitive web projects that challenged the widely held belief that everything on the web should be frictionless. One of their first contributions was their own site, wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, which when you first visit, looks like nothing more than a hackers workstation, unintelligible green characters on a black background. It’s only when you view the source code of the site that you find a hidden gallery of ASCII drawings embedded within. Click around the site a bit and you’ll find yourself tied to an endless string of hyperlinks, hopping from one page to the next, with no real rhyme or reason to tie them altogether. It is almost pure web id, unleashed structurally to engage your curiosity and make use of the web’s most primal feature: the link.

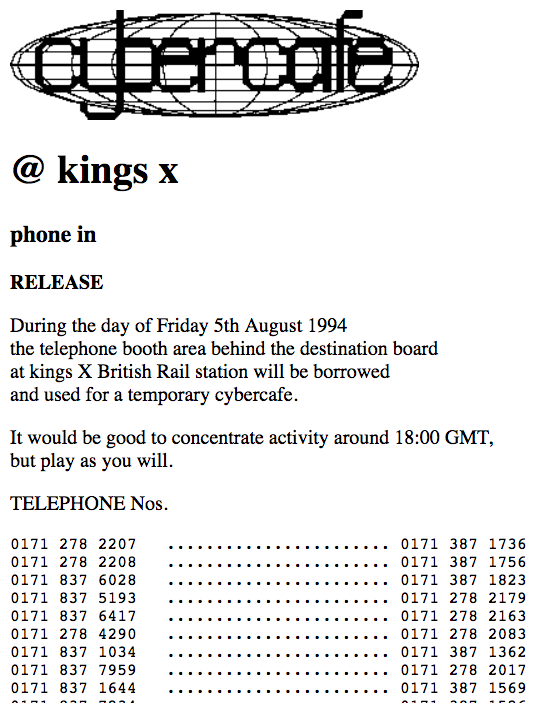

There were other members of net.art whose work was far more technically simple, choosing instead to subvert the expectations of what a webpage could and should be. Heath Bunting, for instance, created a simple white web page that listed every single number for a public payphone in King’s Cross Station in London. Visitors were instructed to call at certain time, at which point you might be connected to a fellow net.art follower who arrived at the right time, or a random and curious passerby.

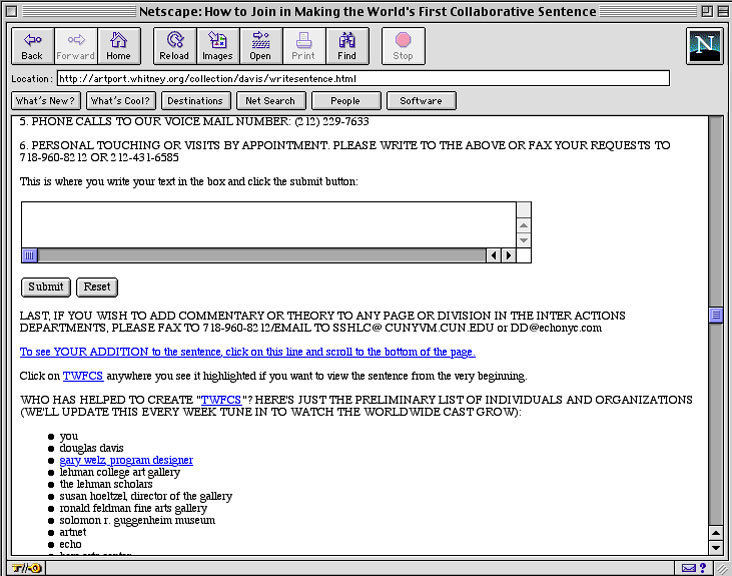

Douglas Davis, who’s work falls a bit outside the confines of the net.art movement strictly speaking, nevertheless created The World’s First Collaborative Sentence (pictured above), a page with a webform that allowed visitors to contribute a chunk of text to the web’s longest ongoing and non-sensical sentence (that’s still around by the way).

The web’s a particularly versatile medium because of how fundamentally collaborative it is. We forget that sometimes, but the web’s superpower is connection. The nettime mailing list, and the discussion and community that formed around it, was as important as any one creator’s website or experiment. The web’s homogeneity was created by people, and there’s nothing about the medium that says everything needs to look the same. One of the stated goals of net.art was to push back on the commercialization of the web, and they did so by discussing alternatives to the mainstream web. So, a lot of their experiments were simple, and not every single one of them landed, but in their crudeness was the beauty of exploration, a uniqueness that you couldn’t find anywhere else. They created works of art that were vast and immersive, and intimate and personal.

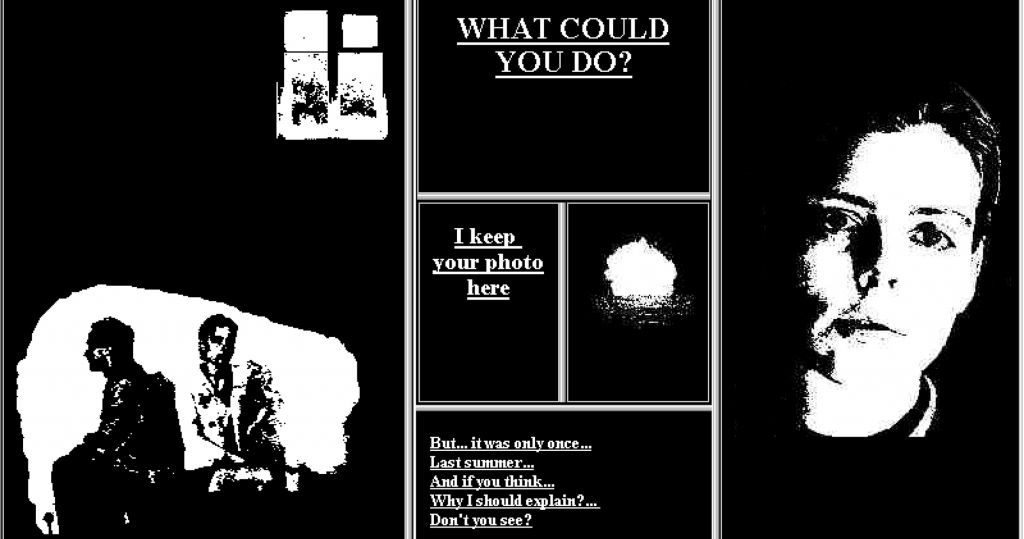

I was particularly fascinated by net artists who merged personally-driven storytelling with impressive technical chops. Olia Lialina created what I can only describe as hypertext prose in her piece, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, a series of animations and webpages embedded inside of alternating frames that creates an interactive, almost cinematic experience. It tells the semi-autobiographical story of a woman reuniting with her lover after he returns from war. It’s magic is in how that story is told, and you make your way through it anyway you choose, jumping between chapters with the click of a mouse.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn used similar techniques to tell their own story. They met online, and it was through Internet art that their romantic relationship blossomed. They merged their two sites into a single destination called Entropy8Zuper!. Their love for one another had grown over the years, and as it did, they sent each other webpages as sort of love letters shared between the two. The pages consisted of poetry, animations, and audio and video clips, ranging in depth and complexity. One of their first major collaborations was to share this collection of love letters on their own site, bringing others into the intimacy of their relationship and demonstrating their dedication to the openness of the web.

Fairly often, net.art members would meet in person, at conferences or academic events. This was an integral part of the movement, and if not for their frequent in-person gatherings, they would not have grown so quickly.

It was at one such event that Vuk Cosic, Alexei Shulgin, and Heath Bunting, three original members of net.art, decided to joke a bit about the death of the movement. As Cosic explains:

In the autumn of 1998 Heath invited all of us to Banff, which is a wonderful place in the Canadian Rocky Mountains where artists go to die. The occasion was a conference entitled “Curating and Conserving New Media”, where very eminent art leaders and statesmen were to discuss our destiny in eternity. So it was necessary to hold a press conference right there and declare the death of net.art. I thought of that as a cool situational performance also reflecting the hated professionalization of our field. Instead it became a useful parenthesis with which to close a period that we now call heroic. It also did a slight disservice to net.art, giving the wrong kind of signal to the literal types that happen to dominate.

The truth of course, is that net.art didn’t die in 1998. In fact, it’d be hard to say it’s ever died at all. Its influence, however, has certainly waned and though Internet art continues on the web, much of its intent and collaborative organization has faded away. However, there remains many dedicated to its future.

My discovery of net.art struck me particularly hard because we have arrived at a moment on the web when our future is worryingly uncertain. And yet, there is a kind of freedom in that. We’ve been shaken into the realization that a centralized web controlled by four or five major tech companies (and I don’t feel as if I have to list them) simply does not have to be the reality unless we let it be.

The net.art movement, and all of its magnificent creations, is a wonderful story because it’s about a whole lot of free thinking individuals feeling around in the dark and not taking for granted what the web was and what it could be. And as I read more about it, I realized that if we play our cards right, we’re poised for another moment just like it. The web is once again being deconstructed by its users in new and different ways. You can see it in tools like CodePen and Glitch, which lower the barrier to entry for folks that want to experiment with web technologies. People are building simple and complex things on these platforms, and whole communities have sprung up to encourage collaboration and sharing. There’s no monetization strategies or KPI’s built into these experiments. Their creators just want to see something new on the web.

You can see it in the language of the web which has evolved beyond simple text to a world of layered reference and moving images. When teenagers learn how to communicate in between the lines of established social networks with layered ironic references and Finsta accounts. They’ve developed a way to be private way out in the open, and we should all take notice.

You can also see the net.art influence in the own-your-own-data mantra of movements like IndieWeb, and the blog what you know spirit of Weeknotes. Or what about those that are encouraging us to keep the web weird or to just write. Or the fact that web standards are finally catching up to the point where we don’t need Facebook and Twitter to talk and share things with friends anymore. I guess what I’m saying is, the lessons of net.art are alive and well whenever someone picks up their own domain and does whatever the hell they want with it. It’s all around us, you just have a look. So go get inspired, and go make something.

Leave a Reply